. . . the professor said, “you should keep composing.” His words kept echoing in my mind. Just who was this person? What did he know? Why should his words change my life?

He was a great teacher, probably the greatest teacher in the United States. I have no doubt.

— George Balch Wilson (1927-2021) American composer and teacher

. . . one of the seminal figures in the musical life of this country in the twentieth century. During his year at Alabama, all who came into contact with Ross Lee Finney were warmed at the fire of his enthusiasm, as they were inspired by his dedication to music and musical composition. Not only the young composers who studied under him, but the whole musical and academic community felt the exhilarating effect of his presence.

— Frederic Goossen (1927-2011) American composer and teacher

Writing musical notation on a page by hand is tedious. Besides the physical energy, as one carefully writes note after note, thoughts often run through your head — Who will hear the finished product? Will anyone care? Is it any good? This exhausting task can sometimes feel useless.

Personally, it is difficult for me, in the moment of composing, to make tangible what I hear in my head. My brain and hand can’t keep up with the notes and melodies running through my inner ear. The notes keep flowing in my mind, but I have to stop and write them down before I lose them. Don’t get me wrong, it is not all dictation. But for me, it usually begins that way. Then I have to work on the material to create a logical musical composition.

Computers make it easier than before. However, that imposes another layer—mastery of the technology. And, even though computers make it easier in many ways—it does not take away the tedium of deciding on every note for every voice or instrument.

None of this is a complaint, but rather an effort to describe the process for a “classical” composer. Other types of music are created very differently.

It’s not hearing what you write, but imagining it.

— Ross Lee Finney (1906-1997) American composer and teacher

By far the most important composer, the one who has had the biggest influence on me, is Ross Lee Finney. I would not be a composer or songwriter if I had not met him. Ross Lee Finney was the first person to hold The University of Alabama’s endowed chair in music. This was during the 1982-83 school year. Four words he said to me are why I am a composer and songwriter.

How wonderful to be in your twenties, in the twenties, in Paris.

— Ross Lee Finney

Finney was widely regarded as a composer of music at a high level of craft and expressiveness. He studied with Nadia Boulanger in Paris in the 1920s, with Edward Burlingame Hill at Harvard in 1929, and did private studies with Alban Berg and Roger Sessions in the 1930’s. During his career he taught at several colleges and universities including the University of Michigan School of Music. One of his well-known traits was the ability to find and develop young composers.

Finney was awarded a Pulitzer Scholarship in 1937, Guggenheim Fellowships in 1937 and 1947, the Boston Symphony Award in 1954, a Rockefeller Foundation grant in 1955, an Institute of Arts and Letters grant in 1956, and was composer-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome in 1960.

My husband, Gary, was a master’s student in composition and Finney’s assistant at The University of Alabama when Finney was the endowed chair. Finney taught a composition class for non-composers and Gary talked me into taking the class. (I think mostly because they needed more people in the class.)

I don’t remember a lot of specifics about the class—there were lectures and some private lessons to work on our compositions. One day, as I recall, Finney brought a guitar to class. During that session, he sat on the piano bench, pulled out his guitar, and proceeded to strum some chords. He then sang “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie.” It seemed like an odd thing to do. This class was about serious, classical music composition.

I did not understand at the time why someone who wrote complicated, intellectual music based on hexachords would stop in the middle of our class and play a song. Nonetheless, that image stayed with me all these years.

I did not think much about it at the time—however, that moment made a huge impression on me. In retrospect, I realize he was showing us the importance of melody and especially in the American heritage of folk music.

Finney’s mid to late music was rooted in a twelve-tone system made up of two symmetrical hexachords. That makes much of his music (to me) complex and hard to understand. It wasn’t until I did research that I discovered some of his earlier music. In one interview he said, “My style certainly has roots in the fact that I have always sung with guitar ever since my childhood in North Dakota. I have given guitar and folksong concerts all over Europe. The voice, the melodic fabric, is very important to me, but on the other hand I am interested also in all sorts of complex mathematical things that have to do with music.” The voice, the melodic fabric being important . . . that explains a lot to me!

You Should Keep Composing

Why did his presence have a profound influence on me? At the end of the semester, Gary and I were married on May 7. Our friends and professors were all invited. Finney and his wife attended with Shirley and Dr. Fred Goossen (composition professor at the university). At the wedding reception I was talking to Mr. Finney and he said I should keep composing. That is all I remember. I do not know how he meant that . . . Should I really be a composer, I should do it for fun . . . or, what?

I wish I had asked him exactly what he meant . . . but I was preoccupied with being married and starting a new life. It wasn’t until several hours later that I mentioned this to Gary.

The piece I wrote during that semester with Finney was for clarinet and piano duet. Everyone’s composition was performed in class at the end of the semester. I don’t recall anything he said about it. Somehow, it must have made an impression on him. The performance from my master’s degree recital is here:

During the summer I had planned to continue work on a master’s degree in voice. My long-range plans were to go to the Netherlands and study voice. I wanted to sing early and Baroque music. Somehow that desire faded and instead I began working on a degree in composition. And, I must say it was the first time in my music career that I did not feel like I was beating my head against the wall. The composition faculty treated me as an equal. They liked my compositions.

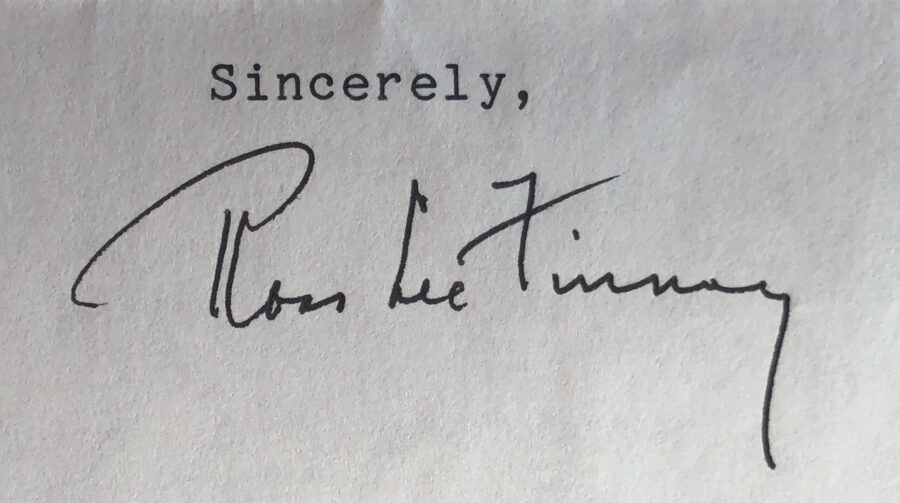

After my master’s composition recital in 1988, I sent Ross Lee Finney a tape of the recital. He wrote me a nice letter after listening. His first sentence was: “I have very much enjoyed listening to the tape you gave me, and I am impressed with how much you have advanced as a composer.” He wrote comments about each piece, then offered general advice about composition. His last paragraph began: “But keep on composing.”

I can’t say that I never considered composing. I had taken a class in twentieth century composition techniques when I attended another college for a semester. We used the book, Twentieth-Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice by Vincent Persichetti. The book explains various techniques in order to dissect and understand twentieth-century music. In the class, we had assignments each week to write a small composition using one of the techniques. I wrote about ten or twelve small pieces that semester—all with varying tonal structures and using different forces . . . from organ, piano, solo voice, to avant-garde music concrete using sounds around me.

Admittedly, I have only composed sporadically since 1988. I really began to work seriously again in about 2006. I have thought a lot about that semester that I studied with Finney and, I have thought a lot about him. He was a very famous, important figure in American music—both as a composer and a teacher. His forthright, mid-western temperament would never allow him to say something unless he honestly thought it was true. I am astounded as I look back and realize how different my life would be if I had not met him and if he had not said those words to me. I do not think I would have become a composer—or more precisely, realized that I am a composer.

Finney’s words below are framed and hanging on the wall in my office. They speak not only to composition, but to music as a whole.

Music is a continuity of gestures.

Shape is a device to hold a piece together

— Ross Lee Finney

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.